The common denominator shared by all winners of the 24 Hours of Le Mans is staggering talent. The likes of Fernando Alonso, Tazio Nuvolari and Jacky Ickx are all recognised as legendary drivers of the greatest endurance race in the world. Among them, a certain "John Winter" who triumphed in 1985 with renowned teammates Klaus Ludwig and Paolo Barilla. The alias masked an enigmatic but touching and grandiose champion.

For Mom

In the early 1950s, the picturesque city of Bremen in northwest Germany was licking its wounds after World War II. Since the end of the conflict, the affluent Krages family had been trying to rebuild its business, namely the exploitation, processing and sale of timber. From the Landhaus Krages, the family villa, young Louis Krages honoured his destiny, following in the footsteps of his father – whom he barely knew – and grandfather of the same name, in the world of conifers and deciduous trees.

In his 20s, Krages pursued his passion for car racing. With consideration for his mother who would have deemed the hobby dangerous, and also to avoid attracting media attention due to his well-known last name, he initially adopted the tongue-in-cheek alias "Peter Wood," then switched to "John Winter" for no clear reason. On race weekends, he would tell his family he was attending a wedding or going out with friends. His reputation at the regional level gained steam, eventually paving the way for a first participation in the 24 Hours of Le Mans.

In 1978, at the age of 28, Winter raced in DRM, the German touring car championship, in a Porsche 935-77 fielded by Kremer Racing. Luckily, the famous outfit was also entered in the 24 Hours. Along with teammates Dieter Schornstein and Philippe Gurdjian, Winter failed to complete the distance sufficient to make it into the classification.

Krages shared the magnificent 935 with none other than Philippe Gurdjian, gentleman driver, future Grand Prix organiser and one of the most famous behind the scenes players in Formula 1 between 1980 and 2000.

Porsche for Life

His mother still in the dark, he travelled the world with the Kremer brothers, driving their Porsches, with one exception. In 1979, he took the wheel of a BMW M1 Procar for one race, without much success. Winter returned to Le Mans, with Gurdjian and Alex Plankenhorn, in a very powerful Porsche 935-K3. This time, the results were much more favourable. The trio qualified in seventh position during qualifying, then finished fifth in the Group 5 SP category.

Kremer Racing kept Winter in DRM, but decided not to retain him for the 24 Hours. For four years, he struggled to find his place, and only made a few select appearances. In 1983, he was hired to drive Joest Racing's Porsche 956. It took Winter a full year to master the Group C beast. Meanwhile, Reinhold Joest's team was climbing the ranks of endurance racing. In the Interserie – another German sports car championship – as in the world championship, he gave his all, returning to Le Mans in 1984 at the wheel of a Joest Racing 956 bought by his friend Dieter Schornstein. Volkert Merl completed the all-German driver line-up. The crew finished fifth overall, providing the necessary encouragement for Winter to stay in the game.

An Hour Fifteen of Bliss

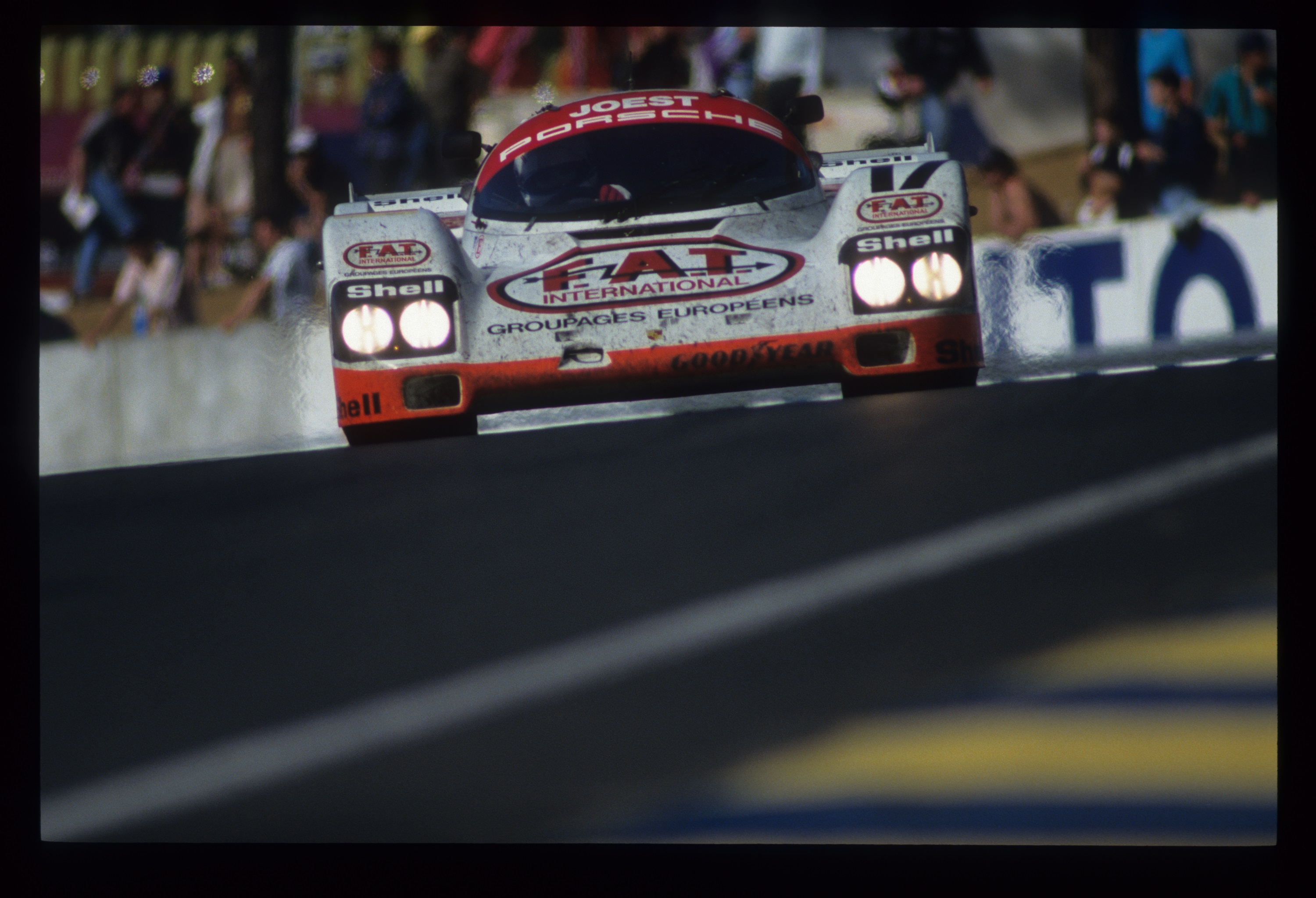

Not your typical gentleman driver, Winter took part in the testing and fine-tuning of the cars he raced. He never really felt like a true professional driver, though he did share prototypes with some top names of the day. Joest Racing won the 24 Hours in 1984 in the absence of the works Porsches, then called on Winter in 1985 to take the helm of the #7 956B winner the previous year. He joined forces with Paolo Barilla (Barilla pastas) and 1984 winner Klaus Ludwig. In reality, he was only there in the event of a problem because his place was paid for. The new works Porsche 962Cs were formidable, but the strict nature of the consumption regulations at the time prevented the cars from performing at peak level right from the start.

With a livery designed by NewMan, the Joest team's Porsche 956s have reached icon status over the years.

Let the games begin. Joest's #7 Porsche 956B and the one entered by Richard Lloyd Racing played tag, driven by Barilla and Ludwig respectively, overtaking each other and exchanging first position to consume less fuel. When the official 962Cs dropped out of the race, the team set its sights on the top step of the podium, with Winter watching from the sidelines, However, at 09:00 on Sunday, as Joest was almost certain to win, Jean-Claude Andruet ruptured a tyre on his WM at Mulsanne. The safety car was deployed, and Winter was handed the wheel to give the two pros a break. For one hour and 15 minutes, the German driver got to live his dream in P1 at the legendary 24 Hours of Le Mans. Though far from being a star, the exposure was too great. Upon his return to Germany, Winter rarely dared leave his home, but when he did, he always sported a cap to avoid being recognised.

The chassis 956-117 achieved the rare feat of two victories at the 24 Hours.

Stepping into the Light

Obviously, it was impossible to remain anonymous after winning the biggest race in the world. Winter's mother immediately learned of her son's victory in a newspaper, but much to his surprise, she was elated and encouraged him to carry on, even watching his races on TV. Though he'd only taken the wheel for a little more than an hour, soon the offers came pouring in. He took the start in the 24 Hours with Ludwig and Barilla in 1986. As incredible as it may seem, Joest's #7 956 was once again a contender for the win against the works cars. Unfortunately, engine failure squashed the team's chances early Sunday morning. Over the years, Winter cultivated a fairly in-depth knowledge of the Porsche prototype, travelling the globe chasing podium finishes.

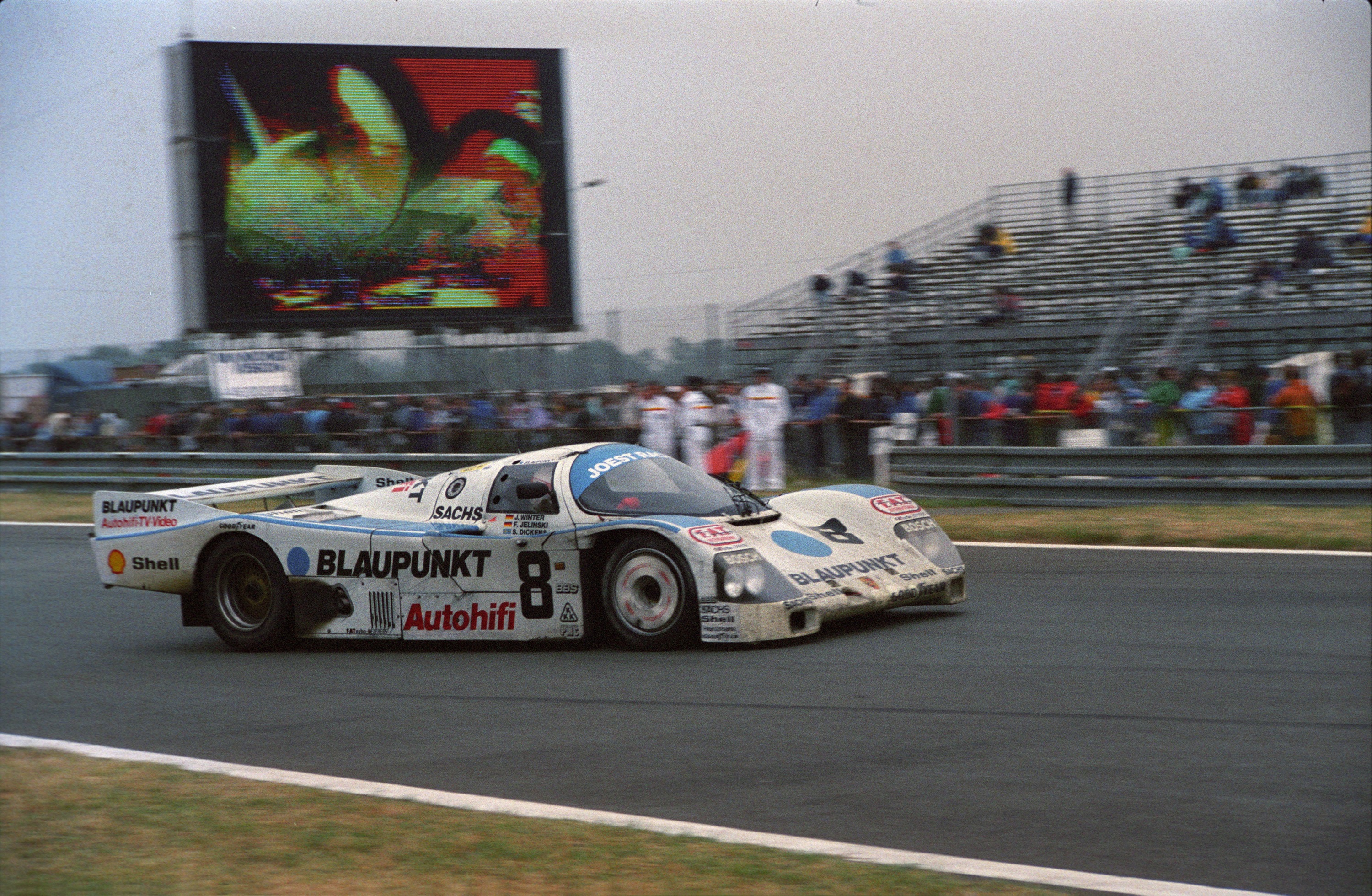

After a successful 1987 season, he returned to Le Mans the next year. Still representing Joest, his spot was covered by Blaupunkt, a major German electronics manufacturer. Winter took the wheel of the #8 962C successor to the 956. He and teammates Frank Jelinski and Stanley Dickens finished heroically in third place, an impressive showing given the level of competition brought by the official Porsche team and Jaguar.

Louis Krages came from an affluent family, who he always claimed did not fund his racing activities. His place was paid for by sponsors like Minolta and Blaupunkt.

Unhappy Epilogue

The German driver did not slow down after turning 40. From 1989 to 1993, he took part in the 24 Hours of Le Mans four times, always with Joest. Most of his races ended in retirements, but he stayed in the fight. In addition to winning the Porsche Cup in 1988 and 1991, he reached the top step on the podium at the Rolex 24 at Daytona along with Jelinski, Hurley Haywood, Henri Pescarolo and Bob Wollek. Winter left prototype racing at the end of 1993 to focus on a new adventure: Joest Racing recruited him for its DTM programme, the renowned German touring championship replacing DRM.

He took the wheel of the equally famous Opel Calibra V6 4x4. At the AVUS circuit near Berlin, Winter lost control of the car at the start of the race, ramming the Opel into a barrier at high speed where it instantly caught fire. Luckily, he did not sustain any serious injuries. Winter laced up his boots one last time in 1995 in a Mercedes-Zakspeed in DTM, this time proudly displaying the name Krages on the rear window of his C-Class V6.

He only crossed the finish line once in his four participations between 1989 and 1993, in eighth place in 1990. Three years later, the engine of this 962C failed on Sunday morning.

Nothing was ever the same after the accident. The family business was suffering financially despite its prestige. In the mid-1990s, Winter was forced to sell the company to the Finnish timber giant Finnforest (now Metsä Group). Divorced from his second wife, he began making wooden toys for children. He moved to Atlanta in the U.S. in order to fulfill this new dream, but things did not work out for him.

Winter's lifeless body was discoverd in January 2001 by the police. The circumstances of his death remain unclear, but a thorough investigation carried out by the Atlanta Police Department suggest suicide.

The story of Louis Krages, a.k.a. John Winter, is above all a story of pursuing one's passion. He rejected his inherited fate in favour of taking on extraordinary challenges and will forever be remembered as an outstanding member of the 24 Hours of Le Mans hall of fame.